Story by Evan Dunstone

There are four kinds of furniture designers. Which one are you and how can you develop your personal style?

There is so much white noise on design these days that it is little wonder that we poor woodworkers get confused. What is design anyway? Is it fashion, interpretation or experimentation? What do we mean by contemporary design? Is it an aesthetic or an approach? How do we develop a personal style?

I believe there are four basic approaches to the craft of woodworking, which by definition leads to four fundamental approaches to design. By understanding how you make, you will better understand how to approach designing. Developing a personal style really depends on how you evolve as a maker and how you relate to the material.

The technique driven designer

Some makers love the process of well evolved techniques and will find any excuse to employ them. Anyone who longs to make cabriole legs or cut dovetails for the sake of it falls into this category. The cabriole leg has a long evolution and is highly refined. You can measure your understanding of the form by comparing it to the world’s best examples. Virtuoso exponents of the technique driven designer will make beautiful text book furniture but will be defined by their craftsmanship rather than their design capacity. They generally have nothing particularly new to say as designers, but can still develop a personal style within the confines of their palette of techniques. Boston’s (USA) North Bennett Street School is the high altar of the technique driven designer.

It is easy to take for granted the skill of the technique driven designer. Because the techniques are so well documented, we can fall into the trap of saying ‘so what, it all comes out of a book’. Because the form is so well explored and defined, we expect nothing but perfection. This is more than unfair, because we have the luxury of looking at the best examples over hundreds of years of development and comparing it to a contemporary effort. Good work is good work, irrespective of when it was made.

In Australia, I would suggest Geoff Hannah and Eugene Zacharewicz would fit this category. Their work is instantly recognisable as their own, yet the designs are also rooted in tradition and technique.

Below: Eugene Zacharewicz, Art Deco Bornagain Box

The naïve designer

The naïve designer is usually the untrained maker who is moved by the material in a visceral way. Australia abounds with naïve designers because we have spectacular timber and an under-developed national style of craftsmanship and design. The naïve designer usually starts with a raw piece of timber and the design evolves organically.

It is often difficult for the naïve designer to develop a really distinctive personal style. Often a little knowledge (usually after some spectacular disasters) spoils the innocence of the approach and the effect is lost. Furniture making has some fundamental rules that, once understood, force the maker to conform. The most successful naïve designers are actually closer to sculptors in spirit than furniture makers. Their work is often not very practical as furniture (such as a ‘chair’ carved with a chainsaw from a red gum stump) but occasionally someone gets it right and does interesting work. I confess that I do not respond well to the naïve designer, despite the fact that I share their love of and respect for fine timber.

Below: Michael Lehntonen, red ironbark and red forest gum Bench Chair

The art furniture designer

Art furniture designers want to maker statement pieces. They consider themselves as visual artists and see furniture as their palette. A successful piece would have the same sort of effect on a room that a successful painting would. The practicality of the furniture is sometimes not a major consideration and indeed many pieces rely on being impractical to make the point. An excellent example of this was at the recent Woodworks 2005 (see review in AWR#50) run by the VWA where Adrian Salter exhibited a chair wrapped in barbed wire.

There are many art furniture designers who strive to make their work practical and functional, while still making strong visual statements. Australia’s Helmut Lueckenhausen would fall into this category. His work is functional, intellectual and visually strong. If you walked into a room containing one of his pieces, your eye would be compelled to look.

Below: Geoff Hague, Landscape Desk, various timbers

The progressive designer

A progressive designer aims to work just within their pallet of techniques and knowledge while still stretching themselves a little more with each design. They place no particular emphasis on a set of techniques and they tend to be focused on the whole piece rather than particular elements of it. Their ultimate aim is to be free of technique rather than be bound by certain techniques. You can spot their early work because it is usually a simple design well executed rather than a poorly made complex design.

Many professionals are progressive designers by necessity. If you are going to sell your work it must be appealing and well made, so you have to start conservatively. If you have done a traditional apprenticeship, your training will have favored the progressive approach.

I suspect it takes longer to develop a personal style as a progressive, but I also think there are great rewards to be had. In Australia, John Comacchio is a good example of a progressive designer. He went through quite a period where his work was really well made, well proportioned and well finished but his style had not fully developed into a complete ‘look’. Nowadays, his work is so distinctive and resolved that you can spot one of his pieces from across the street.

The ability to design evolves in the same way that our ability to make (hopefully) evolves. Ignore fashions and trends and focus instead on why and how you make. If a particular style of furniture appeals to you, ask yourself why: is it because you like the function, the techniques employed, the shapes, the historical context or the timber used? Generally, it will be a combination of all of the above. Working wood successfully is often about having clarity of intent: extend that clarity of intent to your designing as well and suddenly

you will develop your own style.

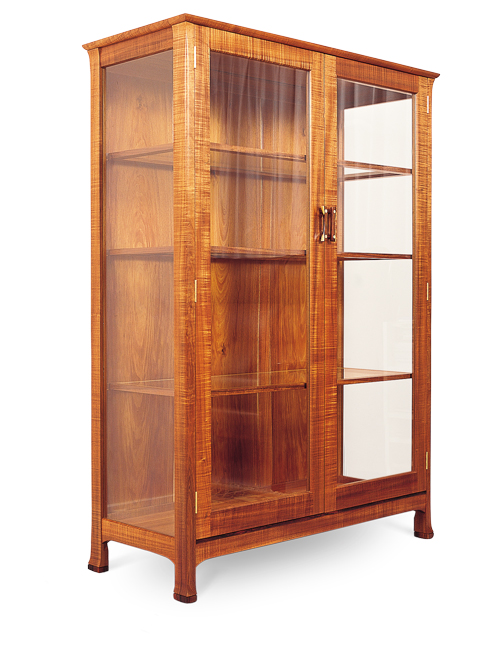

Below: John Commachio, Display Cabinet, blackwood

Evan Dunstone is a furniture designer and maker in Queanbeyan, NSW. Learn more at www.dunstonedesign.com.au