Sharpening is one of the most fundamental woodworking skills, and using sharp tools is one of the greatest of woodworking’s many pleasures. But while learning how to sharpen is fairly simple in theory, it can be frustratingly difficult in practice.

Even knowing when a tool is sharp is difficult because it is so relative. What I think is sharp and what you think is sharp might be completely different. So we can be talking about the same thing, we need a standard. The most accessible one, though it is somewhat rubbery, is the shaving test: if you can shave with it, it is sharp, provided it shaves easily and cleanly, as a sharp razor does. The back of your hand is fine.

Woodworking blades are more than just sharp, however. Each is designed for a purpose which imposes functional requirements on the blade. These functional requirements revolve around bevel angles, edge shapes (square, skew, straight, curved), blade flatness, steel quality, and so on. Except for steel quality, none of them have anything at all to do with sharpness.

With a reasonable steel, if you polish two intersecting surfaces of any shape to a mirror polish, the line of intersection, the edge, will be razor sharp. The angle of intersection has nothing to do with the sharpness, but does affect how strong the edge will be and how it can be used. The flatness of the surfaces only affects how the edge can be used.

But while these functional requirements have nothing to do with whether or not the edge is sharp, they do affect how we sharpen them. You can’t get a flat surface off a soft buffing wheel or a hollow stone.

Sharpening also requires compromise. This is most noticeable in the choice of bevel angle. A low angle (25° or less) will give an easy blade to use, but the edge will be weak. A high bevel (35° or more) gives us a strong edge, but a hard blade to use (it takes more power to push it through the wood).

The ‘best’ angle is a compromise between ease of use and blade life, and that depends on how and on what the blade will be used. While this can become an area of endless experimentation, for most of us a few variations suffice: 25° for endgrain paring chisels or bevel-up low angle plane blades for use on soft woods; 35° for chisels and plane blades used on very hard woods; 48° for bevel-up, low angle plane blades for use on cranky wood; and 30° for everything else.

With all this in mind, let’s now look at some of the things that can go wrong with the sharpening process.

1. Can you see the problem?

You will be surprised how many problems unravel when you can truly see what is going on, particularly right at the edge. So, if you are 40 or so, an eye test might be in order, and even if you aren’t, a good 10 times magnifying glass will prove to be invaluable.

2. What happens if every time you use a normal bench grinder you burn the steel i.e. turn it blue from overheating?

Buying a wet grinder is one way to solve this simple problem. The overheating usually happens because of one or more of three things: the grinder has the incorrect wheel on it; the wheel is glazed, clogged or dull; or you are applying too much pressure or leaving the blade on the wheel for too long.

Woodworking tools require a soft wheel that breaks down quickly and generates little heat because sharp, fresh grit is being constantly exposed to the blade. An aluminium oxide wheel such as the white Norton 38A 60 JVS is good, but even so it will still clog, glaze or dull if it is not cleaned regularly. I use a diamond wheel dresser to do this, but there are other options available.

Finally, if you use a very light touch, patiently, burning edges need never trouble you again. Don’t hold the tool in your hand, hold it with your finger tips. Constantly test the heat by holding the end of the tool for at least five seconds, and once it gets past warm, rest a while, or dip it in cold water.

Burning is likeliest where the heat can build up quickly, such as on the tip of a skew chisel, or on the corner of a blade. It is also more likely when the steel is very thin, so don’t grind right to the edge of the blade if it is not necessary, but leave a tiny band (about 1/2mm wide) of the old bevel intact at the edge. You can’t do this if the edge has a large nick in it that has to be removed.

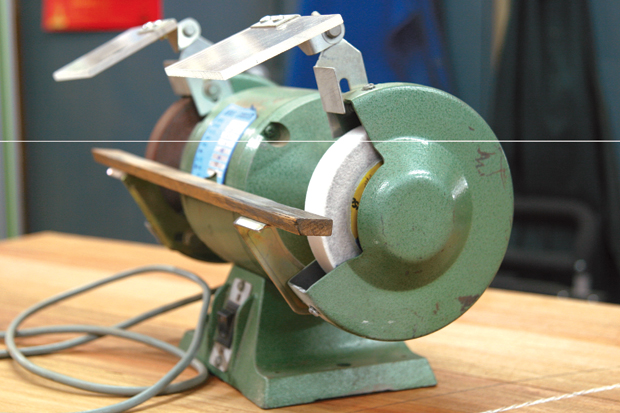

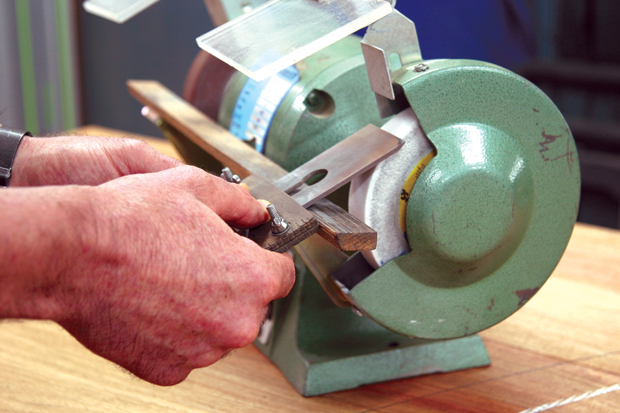

3.How can you avoid ending up with many different partial bevels and a crooked, out of square edge after grinding?

Make a simple jig and adapt the tool rest slightly to use it. This is shown in the photo to the right. By trial and error, establish the projection of the blade past the clamp to give you the angle you want. This will change slowly as your wheel wears to a smaller diameter. You might be able to use a tool you own that already has the required angle to establish your set up.

This jig ensures you always return the blade to the wheel at the same angle, but it will not on its own give you a grind that is even across the blade, especially if your wheel is not perfectly flat and square. If your bevel becomes uneven across the width of the blade, this means some parts are being ground more than others.

You can tell where the grinding is actually happening by the sparks travelling around the wheel. Watching these, you simply avoid grinding the areas where too much has been ground away and concentrate on the areas where not enough has been done. In this way you can slowly bring the grind level across the blade.

If the blade is wider than the grinding wheel I find it easier to get an even grind by passing the blade across the wheel in one direction only. Working both ways creates a dwell period at the end of each pass, which means that more grinding happens at these points. This quickly leads to a curved edge. By carefully cutting in one direction only this can be avoided.

4. Is presenting the blade square to the wheel (or stone) and grinding evenly all that is needed to achieve a square edge?

Unfortunately, no. The blade needs to be of even cross section, and the whole width of the blade needs to be held on the tool rest at all times. An uneven cross section will effectively tip one corner of the blade lower than the other and cause it to be ground more, giving an out of square bevel. Holding the blade unevenly on the tool rest gives the same result for the same reason.

5. Why do I need to grind at all?

The only reason to ever use a grinder is that it is faster than doing it on stones.

6. Why does the mirror polish from the finest stones sometimes only develop in the centre of the honed area, when the coarse stone ground the whole area?

The coarser a water stone is, the softer it is and the quicker it will wear. Thus the coarse stone will develop a hollow before the fine stones, and the mirror image of this hollow will be ground into the blade surface. When this now rounded surface is put to the flatter fine stone, only the top of the round makes contact and is polished. The best solution to this is to stop immediately, grind the coarse stone flat, and then use it to regrind the rounded blade surface to make it flat. Get into the habit of checking all your stones for flatness before you use them.

7. ...but I checked the stones and they were flat.

They appeared to be flat. You usually only have a few seconds to tell if a coarse stone is flat when you place a rule or straight edge across its surface. When the rule is put to the surface, even after it has been ‘dried’ with a rag, the water quickly seeps out of the stone and fills any gap that might be there. To avoid this I always hold the stone up to the light and get it into the best position relative to my eyes before I place the rule across the stone’s surface. I am then able to take full advantage of the few seconds available. Alternatively dry the stone properly then check for flatness.

If the rule is not flat and is not held square to the surface of the stone, the bend in the rule can fit into a hollow in the stone when held out of square one way, and over a hump when out of square the other way. A surer but slower way to check flatness is to draw a series of pencil lines across and down the stone, and then rub it on a flat grinding surface. Any lines remaining delineate a hollow or low area.

8. How do I flatten the stones, and what do I need to watch out for when doing this?

In theory, you simply rub them on a flat surface that holds some grinding material. The most accessible flat surface is a sheet of float glass, the thicker the better (I use 10mm). This needs to be used on a flat surface. On top of the glass use a half sheet of wet and dry sandpaper—about 180 grit for the red or coarse stones, and 320 grit for the fine stones. The fine stones do not seem to work as well if flattened with a coarse paper. Wash the paper clean before moving to a different grit stone, and wash the stone down after using it (a rogue bit of grit can quickly make a mess of a polished surface).

When rubbing, don’t allow the stone to travel beyond the edges of the paper or a hollow might develop in the stone as the centre has more contact with the paper than either end. Also, don’t rub in both directions, or the applied pressure will tend to alternate from end to end of the stone, setting up a rocking action that will result in a hump in the middle of the stone.

You can also apply pressure unevenly across the stone during the pressure stroke, and this can result in the surface having wind. To prevent this, turn the stone end for end every few strokes.

9. How can I tell if hollow stones have rounded the back of my blade?

Apart from using a straight edge, you can make use of the fact that the reflection of a straight line in a flat mirror is itself straight. Conversely, if the reflection is not straight, the surface is not flat. The most convenient straight line to use is the fluorescent tube of an overhead light. Hold the blade in such a way that the reflection of the tube runs across the blade, or down the blade. In both cases look to see if it bends, particularly as it approaches the edge. The shape of any bend is an indication of the position and the form of any hump or hollow.

Another common cause of a bend is the subconscious desire to get the back surface polished as quickly as possible. This is most likely to happen if both hands are not positioned over the stone so as to exert downwards pressure directly onto the stone. If the hand furthest from the edge of the blade is outside the edge of the stone it will exert force on the blade with the mechanical advantage of a lever. If it pushes down it will tend to pivot the blade down over the nearest edge of the stone and this will wear a hollow in this part of the stone and in the part of the blade in contact with it at that point. It will, at the same time, reduce the contact with the stone at the blade edge.

On the other hand, if the subconscious desire to get finished kicks in, it can cause you to lift this outer hand instead and direct the most pressure onto the part of the blade nearest to the edge. This gets the job done, but at the expense of a slightly rounded back.

It is most important, therefore, that both hands be positioned immediately over the stone so as to exert all pressure directly down onto it, and to avoid any possibility of leverage.

10. What causes very narrow chisels to be rounded across the back?

Wide chisels are stable on the stones as you push them back and forth because they are wider than they are thick. However, as the width decreases, the pushing and pulling action sets up a rocking action that increases the pressure on the outer edges of the blade and causes them to wear away faster. In the very narrow chisels the thickness of the chisel increases and makes this effect worse. I find the easiest way to eliminate it is to flatten the backs of narrow chisels lengthwise.

11. Is there any compelling reason to use a honing guide?

I think there is. Only a honing guide will give a flat bevel quickly with certainty. Most bevels honed freehand end up with some degree of round over. This is even more likely to happen if a freehand micro bevel is created. Rounded edges create a number of serious problems. The worst is that it makes it almost impossible to know exactly which part of the round bevel is actually in contact with the stone at any instant. You might think you are honing the edge but find on examination that you have been honing the shoulder without touching the edge. Then, when you again put the blade on the stone, it is impossible to be sure that you have returned to the stone in the same, or better or worse position. In the end, the only way to really know that you are working the edge is to exaggerate your angle (hopefully just a little), but if you do this a few times, you end up not knowing what the angle actually is. This will not affect the sharpness, provided enough work is done on the edge itself (and that is a bit uncertain) but it can affect the function. The final problem is that the amount of work done to the actual edge might only be a small fraction of the total amount done, with the rest being spread over various sections of the bevel behind the edge.

By contrast, with a guide, you can know the angle with as much certainty as you want; you can remove the blade from the stone to examine your progress, and then return the blade to the stone as many times as you want and know that it returns to the same position every time; you know exactly when the edge is in constant contact with the stone; how long it is in contact for; and with a good guide you can return to the same angle with certainty each time you re-sharpen the blade.

This adds up to a compelling argument in favour of a guide. The only arguments against it are simplicity and speed, and these would be powerful if an equally good result could be guaranteed, but it can’t.

12. If my blade only needs a quick touch up, can I use the fine polishing stones only?

In theory you can. The practical problem is that if you do this it is difficult to know exactly where the honing is happening because it is creating a surface the same ‘colour’ as the one already there. This is especially so with a guide that doesn’t hold the blade square automatically. For this reason I like to begin on a stone (the 1000 grit) that gives a contrasting surface finish or colour to the old polished surface, because then I can see where I am grinding.

If you are getting a wedge-shaped bevel and you create a number of facets all of the same surface finish, it becomes impossible to know where you are as well. In this case I simply swap stones to one that gives an easily seen, contrasting surface finish. This might mean temporarily going to a fine stone, making the necessary adjustment, and then returning to a coarse stone to hone out any damage or wear before returning to the fine stones to finish.

13. When I use a guide I often end up with a wedge shaped bevel that does not extend across the blade. What am I doing wrong, and how do I fix this?

Usually, this means the blade is not being presented to the stone square on, but at an angle so that one corner contacts the stone before the other. This is the corner at the fat end of the wedge shape. If you continued long enough the bevel would extend across the blade, but the edge would not be square to the blade. The solution is to push the chisel handle sideways in the honing guide by a small amount, moving it from the fat end of the bevel towards the thin end. You will find it very easy to overcorrect and create the same problem on the other corner of the blade. This can then lead to the problem discussed in 12 above.

Sometimes the initial wedge shaped bevel is not caused by presenting the blade square on, but by an uneven blade cross-section, or an out of square grind. If the grind is out of square you will need a wedge shaped bevel to bring it back to square, so keep going until you have created enough of a new edge to be able to measure or judge its squareness. If necessary adjust again until it is as you want it, and then keep going until the honed edge extends all the way across the blade.

Important though all of these points are, I have not yet mentioned the most intractable problem that almost all woodworkers have with sharpening: we avoid it if we possibly can. If we can’t pick up another sharp tool, we use our sharpest blunt one. But it is useful to remember that the more often we sharpen our tools, the less time we will actually spend sharpening them. This is the rule butchers work by, touching their knives to the steel before each use. This ensures that they are always sharp and that they do not need to lose time on any major resharpening jobs.

The discipline required to do this will be reduced if we make sure that the job is as easy and as pleasant as possible. A dedicated, well lit sharpening area, set up with the necessary equipment is the best way to ensure this.

If all else fails, a last resort might be to own only one plane and one chisel.

Robet Howard is a contributing editor to Australian Wood Review. In the December issue of the magazine (issue 89) he outlines his 5 step process for sharpening. Learn more about Robert here.