How to Make Sliding Doors

Damion Fauser, Kumiko cabinet with sliding doors. Photo: Frank J. Pronesti

Words: Damion Fauser

Photos: Donovan Knowles

Illustration: Graham Sands

Sliding doors can offer many advantages in your woodworking. For a start, not having to fit hinges saves time and expense, and you can also save space if there’s no room for hung doors to swing open. Sliding doors can also add a point of difference and can be made without special equipment.

Doors that slide are common in Japanese design. A few years back I had the privilege of a private tour, including the residence, of the Nakashima Estate in New Hope, Pennsylvania. I was amazed at the simple yet ingenious ways that sliding doors provided storage solutions or concealed certain areas.

1. Recent sliding door console table project by the author. Photo: Naman Briner

I often use sliding doors for some or all of these reasons. Here I’ll show you some of the techniques I use to build them into smaller-scale work such as the console table shown above in photo 1. There are commercial hardware products available for larger work such as built-ins, but I won’t discuss those here.

Anatomy and design

The doors: Sliding doors must be designed with minimal mass in mind to avoid excessive friction. Your choice of species, scale of rails and stiles must all be taken into consideration. For centre panels I’ve used Japanese shoji screens, or veneered panels with resin-honeycomb or 6mm ply as the substrate to keep my sliding doors light. You could also try other materials such as hessian or acrylic. Your design should include additional width in the rails and length in the stiles to allow for the cutting of the long tenons that will run in the grooves.

It’s good practice, for both aesthetics and for a better seal, to overlap the centre stiles of adjacent doors, as shown in photo 2. Factor this in when scaling your doors inside the case opening.

2. The author’s media cabinet showing overlapping centre stiles on the doors.

Because the doors should slide past each other with a minimum reveal it can be difficult to have protruding handles or pulls. Instead, building some form of recess into the stiles can give the fingers some purchase to move the doors along.

The carcase: Your case piece will need grooves for the doors on the inside horizontal surfaces. These can be cut into the panels or into a face frame that is attached afterwards. Both work well, although I do like using a face frame on larger pieces, as thicker stock can give more visual mass.

3. Joinery needs to be carefully designed to prevent exposing the ends of the grooves on the outside of the carcase.

Corner joinery should conceal the grooves within the carcase. Mitres are quick and easy but dovetails are possible too; careful layout will allow you to run your grooves through the socket spaces on your pin boards. Photo 3 shows how mitre keys are used at the ends of some carcase dovetails – one groove runs through the mitre key and the second through the first pin socket.

Finally, interior partitions, drawers or shelves must terminate short of the front face of your carcase to allow the doors to slide freely without any encumbrance.

Grooves and tenons

This is where careful design and planning will pay off. You can choose between having single cheek or double cheek tenons on the doors. I usually reserve single cheek tenons for thinner doors on smaller pieces but this is not a firm rule.

4. Showing rear-set tenons on thinner doors.

Pay careful attention to reference when cutting single cheek tenons, as the front door will have the tenon cut on the rear plane. This is to ensure the front groove is not situated too close to the front edge of the case, and also so the two grooves themselves aren’t located too close together.

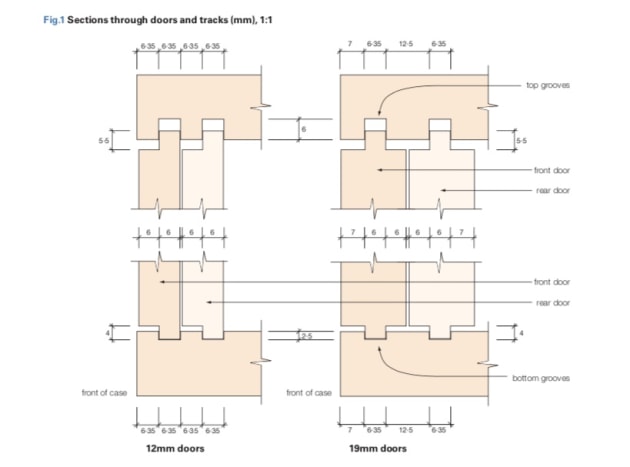

Fig.1 shows details for tenons and grooves for some doors that are 12.7mm or 1/2" thick (photo 4).

When using thicker sections, for example 19mm as shown in fig.1, I like to cut cheeks on both sides of the tenon, but I’m careful to not centre them, instead having a slightly narrower cheek towards the rear of the front door and the front of the rear door. This allows the doors to be installed and removed more easily, but more on this later.

The grooves on the underside of the top of the case also need to be slightly deeper than those on the bottom. This again allows for the doors to be installed and removed.

Building and installing the doors after the carcase is made allows me to work to the reality of the window inside

and also means not having to worry about gluing the carcase together with the doors already installed.

Allowing for extra depth in the top groove gives room to locate the top tenon in its groove and then pivot the bottom of the door into the window before dropping it into the bottom groove. Careful planning will achieve a fine and consistent reveal between the top and bottom edges of the door and the case.

Cutting the tenons

I prefer to make the doors first and cut the tenons on the assembled and sized doors. There are a number of ways to do this however you always need to pay careful attention to referencing, particularly if you’re positioning your tenons off-centre.

5. Using a rebating bit at the router table to cut a tenon cheek.

You could use a handheld router, with either a bearing-guided rebating bit, or a straight bit with a straightedge to guide the router. You’ll get more control using a router table however, and this is one of my preferred methods (photo 5). A sacrificial scrap of sheetgood or timber will guard against damage at the exit point of the cut.

6. Using the sliding table on the saw to cut the tenon cheeks.

At the tablesaw you could use a crosscut sled for precision and control. If you have a sliding table a great way is to mark your tenons on the end of the stock and visually align the blade height off this mark prior to making a test cut (photo 6). Set a stop block to consistently define the shoulders and nibble away at the waste towards the end of the door assembly.

Whilst this operation consists of both ripping and crosscutting, I prefer to use a crosscut blade to minimise the risk of tearout at the exit of the cut. Of course a dado stack will also make short work of this task.

Hand tool purists could also use a rebating or moving fillister plane. In all cases, aim to make your tenons around 0.5–1mm thinner than the width of the grooves to allow for a smooth and unencumbered sliding action.

Cutting the grooves

How you choose to complete this task will depend on the size of your piece or if you are running the grooves into a face frame for attaching to the carcase later. Consider also the width and depth of the grooves, which should be influenced by the thickness of your doors.

7. Using a spiral bit at the router table to cut the grooves.

For a face frame the first option is at the router table, in which case I like to use a spiral bit, as I find straight bits struggle to remove sufficient waste to keep the cut clean (photo 7). Careful planning will allow you to simply flip the components end for end, ensuring your grooves are perfectly symmetrical edge-to-edge. through doors and tracks (mm) full size

For running your grooves in smaller profjects, the tablesaw and router table are good options. For larger pieces, you could use a handheld router with the edge guide attached, a rail-guided saw set for a shallow cut depth, or a plough plane.

Finger recesses for opening

For a small reveal between the front and back doors, there needs to be a way for fingers to grip and move each door. When making kumiko doors on smaller pieces, I like how the patterns provide ample grip when moving the doors. Another option I use is a simple stopped chamfer or hollow on each door stile. This is clean, elegant and allows for either door to be positioned at either end of the carcase and still be opened.

9. Two carefully placed stop blocks on the fence of your router table will enable you to cut easy finger recesses

I usually complete this task at the router table, using a pair of stops blaock as in photo 9. Anchor the first corner against the first stop block, rotate the door into position against the fence, run the pass until the door hits the second stop block and rotate out of the cut once again.

Another sliding option

In AWR#85 I wrote about my hybrid Roubo-style benches. One key feature of this bench is the sliding deadman between the two front legs. In this case, having a groove in the rail isn’t desirable, as it would quickly fill with dust and shavings, preventing the sliding action from working smoothly. Instead I cut a long bottom rail that is beveled on top edges to form a peak in the middle. The trick is then to cut the mating valley in the bottom end of the slider. The angle doesn’t need to be too steep, perhaps 5–7°.

10. Here you can see I’ve boldly marked the layout of the peaked rail for ripping at the tablesaw.

The way to achieve this depends on your saw. I have a European saw, with a sliding table and a right-tilt blade. First dress a wider board to your desired thickness, then tilt the blade, set the blade height to the centre of the thickness of the board and run the board against the rip fence (photo 10). Then flip the board end-for- end and repeat. The resulting offcut will be your peaked rail.

11. Handplaning the chamfers on the peaked rail with a low-angle smoother set for a heavy cut.

If you have a left-tilt blade you could simply run the board against the fence and rip two shallow bevels off the edge of a wider board, then rip the rail away. Alternatively, you could lay out your peak profile on both ends of the board and carefully handplane the two chamfers. In photo 11 you can see I’m using a low-angle smoother to peel off heavy shavings to achieve the effect quickly.

To make the mating cut on the bottom end of the slider on my right-tilt saw, it is most definitely unsafe to run one end against the fence and push the board width- ways past the blade. So, I made a sled jig that supports the board as I run it past the blade.

12. Sled jig and setup for cutting the mating profile on the bottom of the slider.

Leave the blade set at the same angle and raise it to meet the centre of the thickness of your slider. In photo 12 you can see the basic make-up of the jig and the blade set-up. Run the first pass, release the board from the toggle clamps, flip it and run the second pass.

13. Second of the two cuts in progress.

14. The end result, which will run seamlessly on your peaked rail.

You can see this in progress in photo 13 and the end result in photo 14. The top of the sliding deadman is a tenon and groove arrangement as previously described.

Smooth action

To make the doors slide properly, I like to lubricate both the tenons and inside the grooves with a clear paste wax. This is simple to apply and gives a smooth sliding action that is easy to maintain in years to come.

Sliding doors are fun and easy to make. Some basic techniques coupled with careful planning will allow you to explore their use in your projects.

Some of the processes described above are shown in the video below.

Damion Fauser is a furniture designer/maker who lives in Brisbane. He is a regular contributor to Australian Wood Review magazine and teaches woodwork from his Darra workshop. Learnn more at www.damionfauser.com