Words and photos: Charles Mak

As useful as vices, holdfasts, and bench dogs may be for a workbench, they can handle only a portion of a woodworker’s planing needs. Drawers, for example, are too big for a typical front vice, and bench dogs alone can’t properly secure a long board for planing. Here are four bench jigs that will address these needs and undoubtedly see a lot of use in your workshop.

Adjustable planing board

Bench dogs and planing stops are the common workbench accessories used to provide a registration surface for planing. To avoid rotation, the workpiece should be wide enough to span two adjacent dog holes. Sometimes, two stops are used perpendicular to one another to secure the workpiece. For a better solution, I built my own planing board out of plywood that can handle workpieces small and large.

My planing jig is composed of a base, a fixed stop and an adjustable fence with a cleat on the bottom flush with the edge (photo 1).

T-bolts and knobs are used to affix the fence to the base. The fence and the fixed stop willl together capture two edges of the workpiece, keeping it from rotating.

To use the jig, set the fence to the desired width for the workpiece and secure the jig to the bench (photo 2).

The jig can be held on the bench with clamps or holdfasts, or with the cleat clamped in the vice. The cleat has another vital function: It provides extra registration surface for the fence of a plough or rebate plane when I cut grooves or rebates.

Planing batten

To plane the surface of a long board, we typically secure it to a bench dog or two and the tail vice. What if your workbench does not have a tail vice though? A planing batten, used by a British workbench-maker Richard Maguire, is a clever shop-made solution. The batten is simply a strip with a square notch cut at one end (photo 3).

Placing a workpiece between a bench dog and the notch of the batten secured to the workbench will trap the stock between two fixed points. The other beauty of this solution is there is no tightening force from the tail vice and thus thin workpieces will not be distorted using this jig.

To use the batten, place the front edge of the board against a bench dog or planing stop and place the batten with its notch against the far corner of the board at the other end. Hold the batten down on the bench with a holdfast or cramp and plane with the grain as you normally would (photo 4).

Vice rack stop

A bench vice is indispensable for handplaning, especially for endgrain. However, racking, which can damage a vice, occurs when a piece of stock is clamped only at one side of the vice. I have used different types of anti-racking devices, but none is as simple and quick to use as the vice rack stop that American furniture-maker Chris Gouchner came up with. His pair of stops — a narrow one and a thick one for stock of varying thicknesses — are wedges with lips glued or nailed to them.

I altered his design in a couple of ways. First, I made the lip a little larger so the rack stop can rest on top of the vice on one side by itself. Second, instead of gluing lips to the wedges, I made just one lip and two wedges, with magnets on the lip and nails on the wedges to hold them together (photo 5).

When the wedges are worn from use, I simply cut new wedges for the lip.

To use the vice rack stop, open up the vice jaws and place the stop on one side. Clamp the workpiece into position on the other side gently just to keep it from falling and slide the wedge until it stops. Finally, tighten the vice with the desired force (photo 6).

Drawer planing jig

To hold a drawer for planing, you can support it with some scrap plywood as wide as the inner width of the drawer, secured to the workbench. If yours is a twin-screw vice and the drawer to be planed fits between the screws, you can place a pair of supports across workbench top and the vice jaw, and clamp the drawer. Both methods are dependent on a drawer’s size and a new scrap board may be needed for a smaller or larger drawer. Frustrated with their limitations, I developed a planing jig that can support drawers of varying sizes.

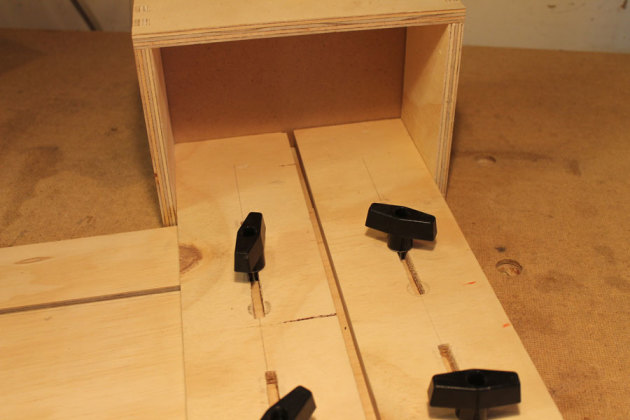

My drawer planing jig is composed of a plywood base with slots cut on the base as well as on the two adjustable arms (photo 7).

Again, T-bolts and knobs are used to fasten the arms to the base. To use the jig, first set the arms to match the inner width and depth of the drawer and secure the jig on the workbench with holdfasts or clamps. Then slide the drawer into the arms, touching the bench apron in its final position (photo 8).

Regardless of the workholding methods that you may be using, these four jigs should add tremendous holding capability to your workbench.

Charles Mak is a regular contributor to Australian Wood Review, a semi-retired businessperson in Alberta, Canada, enjoys writing articles, authoring tricks of the trade, teaching workshops, and woodworking in his shop.

First published in Wood Review, issue 84.