Brian Reid Wall Cabinet

Words and photos: Neil Erasmus

Brian Reid, a furniture maker and good friend of mine from Maine, USA has made a number of what I now call the Brian Reid Wall Cabinet, in different guises. He made the one shown above with doors featuring both marquetry and pierced work while teaching at ESCA School of Wood two years ago. His permission for me to write this article goes without saying.

This project can suit beginner and advanced woodworkers, depending on which construction method you choose. Dowells, biscuits, loose tenons or dominos (as shown here) can be used. The more advanced method employs wedged through mortise and tenon joints with birds beak front edges. A fairly basic set of equipment is required for the first method, while the tenoned version presents a nice challenge for your hand skills.

Cabinet construction

A good, overall size for this cabinet is 1100mm long x 180mm high x 140mm deep, with a thickness in the solid components being around 16mm. The cabinet part should measure roughly 600mm long.

The horizontal shelves and vertical dividers are made of solid wood, while the two sliding doors and back panel are made of 4mm plywood, either pre-veneered, or covered in your choice of veneers. The doors are a perfect opportunity for decorative ideas such as piercing, marquetry or colourful veneer layons.

The overhang of the shelves should be around 50mm or greater, and can be positioned relative to the dividers either symmetrically or asymmetrically. The back panel is housed in a stopped groove, and set in approximately 11mm from the back edge to allow a slotted, key hole cut into the underside of the solid top shelf for mounting purposes. A cabinet of this kind should be relatively lightweight, due to its simple fixing method.

The front has similar stopped grooves in the top and bottom, but not the dividers. The grooves are next to each other and allow the doors to slide past one another. The grooves in the top are twice as deep as the bottom ones so the doors can be raised up and removed. The back edges on both designs are all flush, as are the front ones on the mortise and tenon version. The dividers are set back from the front edge of the shelves by 6mm on the domino version.

Making the cabinet

First determine the proportions, timber choice and layout, and then proceed with an accurate cutting list of all the components. The veneers to the back panel at least, should be pressed onto the slightly oversized, 3–4mm plywood substrate, so this is ready for assembly when all the machining is done. The door veneers can also be pressed at this point, or left until later as they can be placed in position after assembly.

Plane, edge, thickness plane and cut to length all solid components. Orientate the four components and proceed to mark out exactly where the dividers fit into the shelves.

Set up the domino machine with the 6mm cutter for 12 and 28mm deep cuts respectively for the shelves and dividers, then mark out and cut these. A spacer may be necessary if you wish to centre the slots in the divider.

If you choose the stub-tenon and bird’s beak version, mark out the four 8mm tenons and 6mm bird’s beak on the ends of the dividers.

You can then cut these either by hand or against the fence on the bandsaw. Make sure the tenons fit whatever means you choose to cut the mortises.

Mark out for the mortises, by simply transferring the tenon positions. The mortises may be cut by hand or machine, but either way, the cuts need to flare out somewhat to the outside face to accommodate the wedges that will be driven in upon assembly.

I use a special angled platform on my hollow chisel mortising machine which can be flipped over to flare both ends of each mortise . Sacrificial material held under the shelf is very important.

Cut the bird’s beak to the front edge on the tablesaw, using a 45° jig that can be flipped over to allow both angled cuts to be made.

Set up the bandsaw and cut twin slits in the tenons to take the wedges.

Partially fit the tenons into their respective set of mortises so the bird’s beak housing may be knifed and cut. A small router with a 3.2mm cutter is useful for hogging out most of the waste before chiselling to the cut lines.

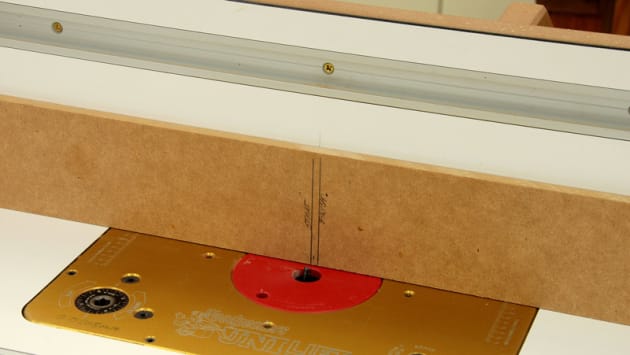

For the two different grooves that will house the sliding doors, set up the router table with a bit that suits the plywood thickness plus its two face veneers, and set its depth at around 5mm, and 11mm. (If instead you use a hand-held router to cut these grooves, set the rotating turret stop and post, one at a depth of 5mm, the other at 11mm). On the router table I dialled those two depths in using a digital height gauge.

Set up the fence to start the cut 11mm away from the edge. If using the router table, you will need to mark the position of the cutter on the fence to facilitate accurate stopped grooves, as the cutter will be hidden from view.

Using the router table, the shelf has to be carefully dropped onto the spinning cutter to start the cut, and then lifted off once the cut has been completed.

For the back panel, groove both dividers and stop-groove both top and bottom shelf just shy of the centre-point of where the dividers meet. Similarly, still with the same depth and fence setting, do the stop-groove at the front of the bottom to house the front sliding door.

Next, change the depth setting to cut 11mm and cut the first groove in the top. Then, move the fence to cut another groove to the inside of the first one, leaving a safe ‘wall’ thickness of around 3–4mm between the two, and, still on the 11mm deep setting, rout out the second groove in the top. Finally, reset the depth to the first setting of 5mm, and complete the grooving of the bottom shelf.

Next comes the bullnose moulding to the front edges of all four solid components, and the ends to the shelves. I used a special router cutter fitted to the router table, and set the fence to ensure the middle of the cutter is barely contacting the wood.

Alternatively, you could simply mark out the parameters of the moulding and handplane with a spokeshave or blockplane. At this point, I would check the back panel for size and cut it down so it will comfortably fit the groove housing in the shelves and dividers.

Next is the glorious task of sanding all parts excepting the easy-to-get- at surfaces that should be done once assembled. It is a small piece, so I would sand by hand with a block, and for the edges I use a specially shaped block that fits nicely over the bull-nosed moulding. Once this has been completed to your satisfaction, you are ready to assemble, using appropriate clamping cauls. Some prefer to finish the inside first — your choice.

Using a small keyhole router cutter and fence, two stopped slots are cut into the underside of the top shelf. Now all that is left to do is to clean up the odd bruise here and there, then to finish the cabinet completely, and hang it to a wall. Measure the distance between the centres of the keyhole slots, fix screws in the wall, and use a level to drop the shelf over the screw heads.

Lastly, the door panels can be sized perfectly to fit the cabinet, and dropped in place. Leave an overlap between the two of about 20mm. I don’t bother with edging the plywood with solid lippings, opting instead to sand them nicely. If desired, a small handle may be set in at one end of each door, but I feel this is unnecessary.

As a wall-mounted piece, this simple design is a perfect canvas to display whatever decorative techniques you choose to feature.